Building without building services: part 2

Comfort in a building is like short a moment of happiness

Part 2 in a series of articles about building without building services. Did you read the first part already? Otherwise, you can read it here.

Close your eyes and imageine you are in your living room. It’s autumn and you are having breakfast on a lazy sunday morning, the space filled with the smell of freshly made coffee and baked bread. Outside a dark cloud drifts away, giving clear sight to the sun. Suddenly, the sun’s rays hit your face, warm and comfortable. That is enjoyment, isn’t it?

Exactly that feeling, the unexpected, but welcome change in your surrounding… The sun during your breakfast or a fresh breeze on a hot summer day; those are the small moments of happiness. And you are not the only one who enjoys it with full pleasure. Whole studies have been performed on this topic which we now call ‘alliesthesia’. In plain language: an experience of short happiness because something changes in your environment and you become extra conscious of the world around you.

From outside in

Enjoying your surroundings and its changeability is done outside. Wouldn’t it be great to also take those moments of joy inside? To make buildings in which we are more aware of the surroundings, buildings that work with the biorythm of people and offer diversity, especially also inside? Research has proven that more daylight, fresh air and sounds in buildings stimulate these types of experiences of joy. Hearing rain on a window gives us a protected feeiling and allowing daylight in and experiencing changing weather makes us aware of the world outside of our workspace.

This hedonistic approach and more specifically looking at what people really find pleasureable demands a different view on the usage of building services. We are, after all, used to buildings having a very constant and static indoor climate. In these types of climatized spaces ‘comfortable’ moments of happiness are difficult to find. With the development of central heating and airconditioning, buildings have often become between 18 and 23 degrees in winter and summer. Illuminance is kept constant at workspaces and noise and draught are banned as if they were criminals.

Rigid

But that is exactly what we call comfort. A case in which we try to create an environment that changes as little as possible with all our might. But is that dominant definition of comfort actually true? And who decided on it? In practice one might find 23 degrees a good temperature, while someone else might work best at a ‘chilling’ 18 degrees. Comfort changes from person to person and that could therefore not have a rigid definition?

Status quo

The status quo is that a device is turned on when a ‘comfort issue’ is present. For an even better comfort we would require even more technology. The ‘best’ techniques for ventilation decide what the healthiest air is you can have in a building. But even the air quality you attain there is not close to outside air quality. And outside air is freely available as well.

The solution

Turning away from those strongly conditioned interior climates and designing more dynamic environments make our buildings healthier and more comfortable for their users. Pleasant buildings with a plethora of spaces and experiences, with fresh air and daylight and in which you experience the outside weather: it is perfectly possible.

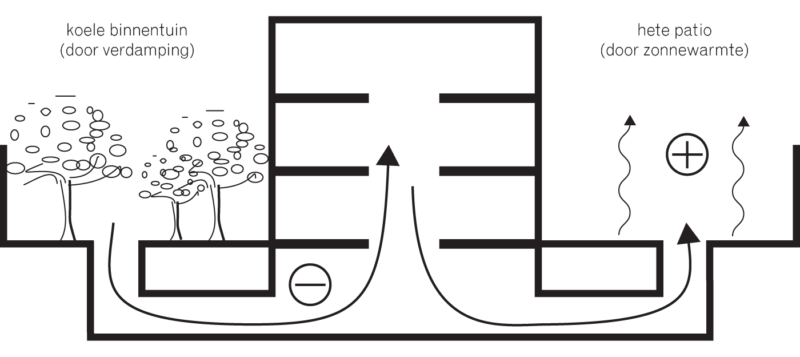

Additionally such buildings don’t even need that many building services to achieve a comfortable indoor climate for most of the year. As long as we use the natural possibilities of orientation, wind direction, soil conditions, materials and designing for the climate. Then we need very little building services -and energy- to heat a building sufficiently and supply it with fresh air. The ancient Egyptians used a combination of underground tunnels and interior gardens to cool their buildings. On the one hand of the building was a cool garden, lushly vegetated (providing evaporative cooling). On the other hand was an empty patio, allowing for the air there to be heated up by the sun. The two gardens were connected with a tunnel and the chimney effect would then pull cool air through the building. By using the elemets at hand smartly, a cool building can already be made without using building services. Comfort, and in great amount happiness.

Next time

Pleasant environments make people happy and that leads to higher performance, more alertness and less illness. Daylight also plays an important role in that. In the next article we dive deeper into the usage of daylight, the influence of that on human psychology and our mood and the (in)sensible ways that it is dealt with currently.

Read part 3 of our blog series about building without installations here.

- Author

- Aldo Vos, Architect-director Broekbakema

- Images

- V-Lodge of Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter

- Photographer

- Sören Harder Nielsen

We are happy to tell you more.

- ir. Aldo Vos

- Architect director